Artists inspiring other artists (English version)

How many times have you heard that in art, everything has been done, everything has already been said and nothing new is to be expected?

Stuart Davis, The Mellow Pad (1945-51) in the exhibition “Stuart Davis: In Full Swing,” at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Credit… Michael Nagle for The New York Times; All Rights Reserved, Estate of Stuart Davis /Licensed by VAGA, New York NYtimes

Nina Chanel Abney, Culture Type

When I was studying art, a long time ago, I kept hearing this statement. And if today, the years have passed and my experience of art has been enriched, I can say that this expression is false, as I have the constant pleasure of discovering new artistic practices, new forms of painting and works and artists that surprise me and that I can rave about!

However, I think I have to admit that this expression also contains some truth. But be warned, if it does, I see something positive in it. Why?

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled, 1981, © Broad Collection, Los Angeles, USA Kazoart

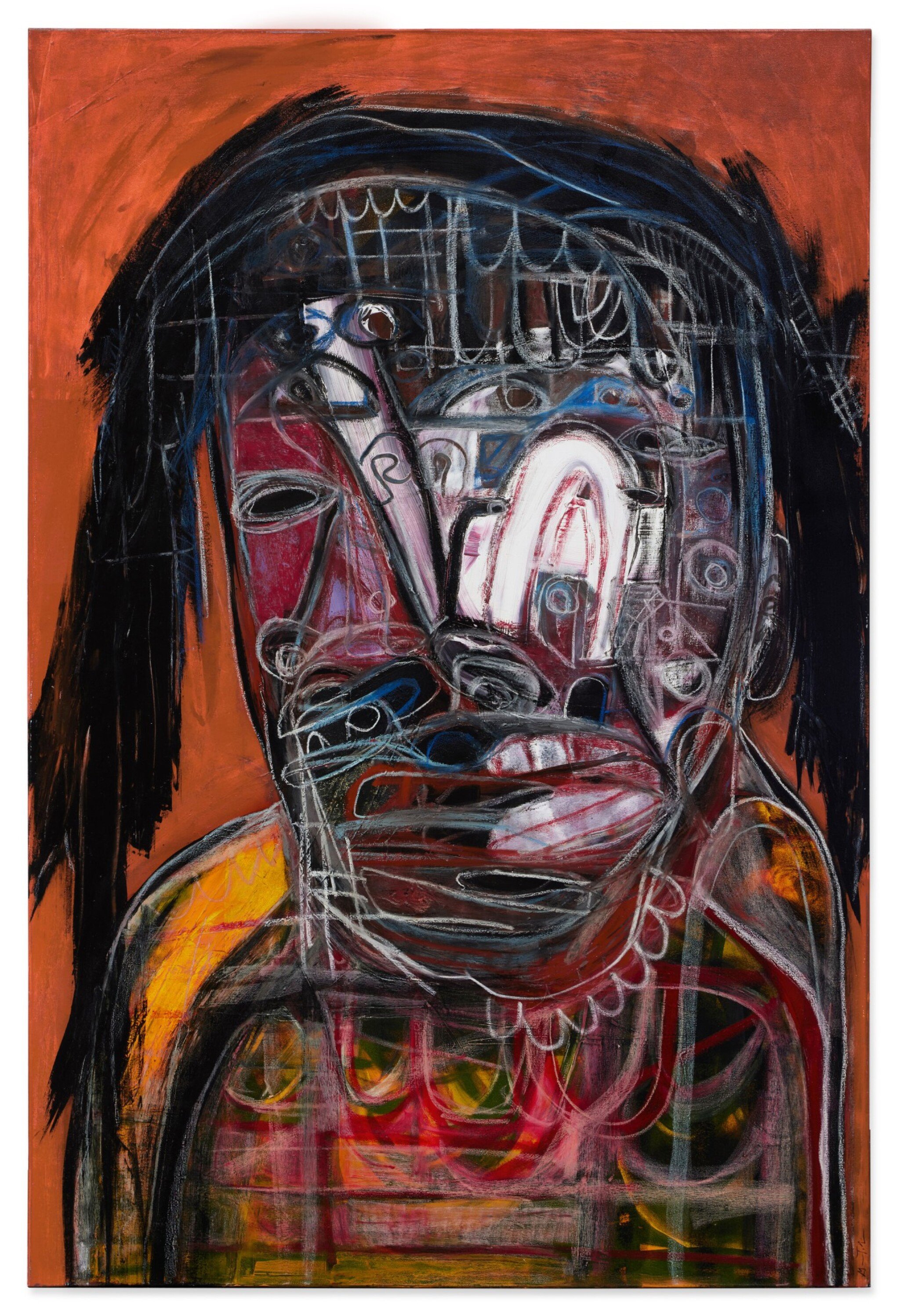

Genesis Tramaine, Hosanna, 2019, acrylic, oilstick and spray paint on canvas, 183 x 122 cm. Sotheby’s

First, because the sources of inspiration, those artistic practices of the past, those artists who lived one, two, three or more generations before us, sometimes slightly forgotten, are thus rediscovered by our contemporaries, allowing us, if we recognize these origins, to be interested in the history of art and to remember how much these artists brought to the world an invaluable contribution.

Mark Rothko, Untitled (Red, Orange), 1968, 233.0 x 176.0 cm, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel Fondation Beyeler

Sterling Ruby, SP288, 2014, Spray paint on synthetic canvas, 243,8 x 213,4 cm (96 x 84 inches) © Sterling Ruby

Also, because the new artists developing in their contemporary time (just like those of the past in their time, respectively... "contemporary"), without however copying their elders, update elements drawn from their work, to adapt them to their individual practices and contribute to the art world with works that speak to us, because having similar concerns to ours. Without really talking about "appropriation" (which is an art form in itself), these elements of inspiration are often formal: ways of painting or sculpting, recognizable techniques that allow us to say at first glance: "inspired by Picasso, Dali, etc." These are obviously the most obvious elements of comparison, because they are visual.

Willem de Kooning, Landscape, 1972. Arthistoryproject

Rita Ackermann, Mama, Skirt on Fire, 2020, Oil, acrylic, pigment, and china marker on canvas, 193 x 190.5 cm / 76 x 75 in © Rita Ackermann. Photo: Jon Etter. Hauser & Wirth

More difficult to grasp are the conceptual elements, the bases of research, because even if they can correspond through the ages, they will not necessarily be visually similar and therefore, to be able to associate them, we will have to call upon our cognitive memory. The example of Marcel Duchamp, with his famous "Ready-Mades" is certainly one of the most obvious, since before him, we used to sculpt wood and marble, and we used to cast bronze (which we continue to do, by the way, by associating it with contemporary practices) and thanks to him, the artists started to recover or use absolutely all the possible and imaginable objects to realize sculptures, henceforth called "installations", etc.

Henri Matisse, Intérieur avec fougère noire, 1948 artnobel

Chris Ofili. The Raising of Lazarus, 2007. Oil and charcoal on linen. 110 x 79 inches. Photo: David Zwirner. imagejournal

After his famous urinal (and before it, Bicycle Wheel, created in 1913! ), artists have notably used bottle caps (1), coffee (2), pollen (3), grease (4), sledges (4), cars (5), excrement (6), sunlight (7), earth (8), lightning (8), television (9), the human body (10), or animals (10), and countless other objects to create their works, all indebted to Duchamp!

Jean Paul Riopelle

Mark Grotjahn, Untitled (Backcountry Capri 54.74), 2021. © Mark Grotjahn. Photo: Douglas M. Parker Studio, and courtesy of Gagosian. occhimagazine

On the other hand, it is certainly less obvious to see that Claes Oldenburg's work is related to 17th, 18th and 19th century still lifes, Warhol's pop portraits to those of 19th century bourgeois, or even the Fayum of 1st century Roman Egypt or Orthodox icons through the centuries, or Mark Rothko's work inspired by Greek mythologies and Friedrich Nietzsche's The Birth of Tragedy.

Edouard Manet, La Négresse, 1862, huile sur toile, 61 x 50 cm

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Citrine by the Ounce, 2014, Doreen Chambers and Philippe Monrougié. © Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Tate

But what are artists doing today with the formal foundations of those of the past (and sometimes, the present)? They are indeed inspired by them, and they transform them, generally adapting them in a consequent way to the techniques of today (notably with the passage from oil to acrylic, the use of spray), to the development of the use of the colors related to their respective times and also, to their respective lives, cultural and geographical contexts. They adapt them to their own relationship with the invisible or their inner demons, such as Yayoi Kusama, to their relationship or misunderstanding of today's society, etc.

Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942, oil on canvas, 84,1 x 152,4 cm. Wikipedia

Stéphane Ducret, Painting Number 3 (#MarkGrotjahn #Gerhard Richter), 2019, Oil, oilstick and pencil on canvas, 208 x 188 x 4 cm. stephaneducretstudio

Now, before ending this publication and since I am also presenting here one of my paintings from the REAL ESTATE series, next to an artwork by Edward Hopper, I have to clarify one important thing, since I know the sources of my inspirations: When I started this series of works, my sources were the works of contemporary artists that I reworked, or that I appropriated, to integrate them into my paintings, sometimes in an obvious way, as here with a drawing by Mark Grotjahn, sometimes in a more subtle way, as here again, with the famous candles by Gerhard Richter.

László Moholy-Nagy, EM 1, 2 & 3 (Telephone Picture), 1924.

Moholy-Nagy wrote that he placed the order with instructions by telephone to an enamel factory in Weimar, Germany, who produced them, providing the paintings with their unofficial title. MoMA & Almine Rech

Donald Judd, Untitled, 1987, Painted aluminum, 30 × 120 × 30 cm (11 3/4 × 47 1/4 × 11 3/4 inches). Judd Foundation

But at no time did I think of Edward Hopper as a source of inspiration! Surprising, when several friends have named this artist in reference to my paintings... So, if I have spoken here of artists inspiring other artists and also published many examples, at no time can I affirm that these inspirations were conscious. Because, as for me, these artists can have, in an unconscious way, woven links with their elders, or even, not to have any knowledge of them: which remains unlikely, though.

26th July 1979: Bridget Riley, British painter and leading figure in the Op Art movement, standing in front of one of her curving 'line' paintings at her studio. (Getty Images)

Philippe-Decrauzat

Picasso had already said it: “Good artists copy, great artists steal.”

But, of course, there is not only the work of other artists that inspire the new ones... So, enough for today, it will perhaps be the subject of another article.

Stéphane Ducret, Buenos Aires, April 9th, 2023.

La Victoire de Samothrace. Petite galerie du Louvre

Thomas Houseago. Inferno Magazine

1. El Anatsui

2. Jannis Kounellis

3. Wolfgang Laib

4. Joseph Beuys

5. César, John Chamberlain, Richard Prince, etc.

6. Piero Manzoni

7. James Turrell, Olafur Eliasson, etc.

8. Walter De Maria

9. Nam Jun Paik

10. Wim Delvoye

Alexander Calder, Le Hallebardier, 1971, Sprengel Museum Hannover, Hannover, Germany. 3 minutos de arte & Calder Foundation

Aaron Curry, High Museum of Art. Wanderlust Atlanta